Enabling Accessible TV shows and Educational Media for Children with Disabilities

October 22, 2018

Here’s a reality check: According to the World Health Organization, there are between 93 and 150 million children under the age of 14 living with disabilities worldwide. And in the US, one in 59 kids has autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In fact, nearly 20% of the entire US population—or about one in five Americans—currently lives with some form of cognitive or physical disability. Surprised? Many are.

Across the pond in the UK—where there are 33% more disabled children than a decade ago—a coalition of 60-plus charities led by the Disabled Children’s Partnership published economic research in July revealing a US$1.9-billion funding gap for services needed by disabled children. The report concluded that tens of thousands of disabled kids are missing out on vital help that enables them to do things other children take for granted, like eat, talk, leave the house, attend school and have fun. The situation worsens for disabled children in developing countries as gaps between children with and without disabilities have increased dramatically, according to research from the Global Partnership for Education and the World Bank.

From a children’s media perspective, while the industry is making positive strides to focus on diversity and inclusion with content addressing race, gender and sexual orientation, accurate representation of the disabled community—or representation at all—continues to be a larger challenge. In fact, people with disabilities remain the most marginalized group in Hollywood, according to a 2017 study by American philanthropic group the Ruderman Family Foundation.

The Railway Hero dashboard, a key element of PBS KIDS’ new STEM-learning Cyberchase game, features many customizable accessibility functions and is the result of the “born accessible” approach to design

So how are content producers and game developers addressing children with autism, blindness, deafness, cognitive and physical disabilities? Are TV shows and games being developed to give disabled and non-disabled kids equally engaging experiences?

The answer to this rests in content, games and entertainment experiences that are “born accessible,” the name given to a nascent movement that aims to consider the needs and experiences of users of varying abilities right from the start. Rather than modifying content for disabilities after the fact, leaders in the born-accessible space use disability as creative fodder to develop more inclusive, quality content. And they’ll tell you that the results—whether addressing diversity through representation, technology or hands-on tools—are gratifying.

Universal access

Despite an uphill battle for disabled representation, there has been headway. In April last year, Sesame Workshop’s first autistic Muppet, Julia, made her Sesame Street debut on PBS KIDS and HBO as part of the Workshop’s Sesame Street and Autism: See Amazing in All Children initiative. And Pablo is a popular animated series produced in Ireland by Paper Owl Films, in association with Kavaleer Productions, that stars a five-year-old boy with ASD who uses magical crayons to cope with everyday situations. To date, the groundbreaking CBeebies commission has been picked up by major broadcasters including Universal Kids (US), Nat Geo Kids (Latin America) and Netflix in multiple territories.

Speaking of Netflix, the streaming giant kicked off its audio description (AD) initiative back in 2015 with Daredevil, Marvel’s blind superhero series. And the SVOD now provides more than 7,500 hours of AD globally, covering over 20 languages.

In the digital space, preschool SVOD app Hopster introduced a playroom called Sense last year to help kids, particularly those with autism, develop sensory processing skills. One of the platform’s original shows supporting the initiative, Punky, is about a young girl with Down syndrome. As for gaming, Microsoft recently unveiled an adaptive controller for Xbox that addresses the needs of disabled gamers. And it went one step further by creating an accessible box design to give disabled gamers an empowering unboxing experience. Major toyco Hasbro has also stepped up to the plate this year, launching online resources with Rhode Island’s The Autism Project designed to make play more accessible to kids with developmental disabilities.

According to Matt Kaplowitz, president and founder of New York’s Bridge Multimedia, which focuses on supporting accessible media, more companies are finding ways to create accessible content and spread awareness, but most producers and developers simply don’t know where to begin.

“There is a great willingness from well-intentioned TV producers and game developers to do more for inclusion, but they don’t know how and lack resources,” says Kaplowitz, who chose his line of work largely because he’s the father of a legally blind and visually impaired adult daughter.

Bridging the gap

For nearly 20 years, Bridge has been at the forefront of universal access for educational, entertainment, corporate and governmental applications. Its services include AD in all media formats, including broadcast and cable TV, video, streaming media and online; closed and open captioning; bilingual description and captioning; web development; and cross-disability product design.

Among its many achievements in the kids space, the company partnered with TERC, a non-profit educational org, to launch hands-on science learning tools for autistic students with funding from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). It also leveraged NSF resources to help Vcom3D develop a series of illustrative, interactive 3D sign language dictionaries for students in grades four to eight who are deaf or hard of hearing.

On the broadcasting scene, Bridge received a five-year grant from the US Department of Education (DOE) in 2010 to produce standards-aligned AD for children’s TV on networks including PBS, Cartoon Network, Nick Jr., Universal Kids and ABC. The grant was renewed for another five years in 2016. According to Kaplowitz, the company is currently audio describing around 37 network shows for kids and adults each week.

Bridge’s latest project is Railway Hero, the first accessible and universally designed digital game for PBS KIDS’ hit math series Cyberchase. The STEM-learning HTML5 game is produced by New York’s THIRTEEN Productions for parentco WNET, in collaboration with Bridge and developed by learning and entertainment developer Sudden Industries.

From the ground up

Available for free on the PBS KIDS Games app and at PBSKIDS.org, Railway Herowas designed using a born-accessible approach, with accessibility functions built into the game design from the ground up to aid children with physical and cognitive impairments. Aimed at kids ages six to eight, players join the CyberSquad on a mission to repair the SuperRailway in cyberspace after pieces of its track are stolen by an evil hacker. To fill in the empty spaces, kids must use math and problem-solving strategies including counting, addition and spatial reasoning.

With funding from the US DEO’s Office of Special Education Programs, WNET and Bridge used insights from extensive user testing at the Kentucky School for the Blind and the New York Institute for Special Education to develop accessibility features including customizable text size, color and contrast options; adjustable music, sound effects and voiceover levels; AD and keyboard controls for blind or visually impaired users; captioning for deaf or hard-of-hearing users; and a number of cognitive features like caption controls and audio descriptions.

Railway Hero is the first universally designed game for PBS KIDS’ with math series Cyberchase

“In the gaming space, there hasn’t been a huge amount of work done to create a game from the ground up that appeals to as broad an audience as possible,” says Sandra Sheppard, WNET’s director of children’s and educational media and Cyberchase executive producer.

According to Kristin DiQuollo, also an executive producer on Cyberchase, WNET started onboarding developers in November 2017 after a two-month discovery phase, and the game was completed just eight months later. “It was an ambitious timeline,” she says.

Dashboard confessional

One of the most unique elements of Railway Hero is its dashboard, which lets kids set up the game according to their interests and needs.

“We made sure that any kid will want to engage with it. Even though we know it speaks to specialized audiences, it really speaks to the universal kid,” says Sheppard.

“The game is also fully playable without vision. So if you turn your computer monitor off and turn on the game’s AD, you can navigate it entirely with arrow keys and the description. When we tested with blind children, they were just as excited to earn their stars and beat a level as children with sight, which was a truly validating experience for us.”

As far as device preference for blind children goes, the developers assumed a lot of the kids they tested would use desktop computers, but they quickly learned that all of the visually impaired kids preferred to play on tablets.

“They were heavily supported and had aides to help guide them through the game, but it was great to see. Keyboard hookups for tablets can also be used to access the game’s controls,” says Sheppard.

In terms of the game’s built-in cognitive supports, which are less visible than the dashboard functions, DiQuollo says they are equally important.

“When the Cybership passes over a gap successfully, users will hear lots of ‘hurrays’ and cheers from the kids in the game. Kids are also very supportive if you get a question wrong,” she says.

For Kaplowitz, using the right positive feedback words—especially for kids on the autism spectrum and those with multiple disabilities—is crucial.

“Because these kids are so subjected to failure, they thrive on praise and compliments. But you can’t praise concrete thinkers with confusing phrases like ‘Good job, there’s nothing you can’t do,’ or ‘You hit it out of the ballpark.’ It’s a great compliment, but what ballpark? When concrete thinkers hear these types of expressions, you lose them,” he says.

DiQuollo says the biggest challenge in making the game was the technical aspect of designing Railway Hero for so many different audiences.

“The AD, in particular, was the largest challenge technically because we had to figure out how best to deliver the triggers in the game in ways that made sense,” she says.

Sheppard, on the other hand, says managing expectations was difficult. “For your first accessible game, you are never going to do 100% of what you set out to accomplish, but it’s still important to do as much as you can. Some features we had to give up because of budget and scope, but that is OK,” she says.

Engagement for all

For PBS KIDS, which offers closed captioning for all of its linear shows and AD for the majority of them, applying the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to its digital content has been paying off from an engagement perspective.

Since the pubcaster recently incorporated closed captioning into the PBS KIDS Games app, the closed captioning was activated and kept on more than 2.5 million times in the first month after launch.

PBS KIDS is applying Universal Design Learning (UDL) to its digital content, and closed captioning has been activated more than 2.5 million times on the PBS KIDS Games app

“Accessibility, adaptability and customization across all PBS KIDS platforms is integral to our mission to prepare children for success in school and life,” says Lesli Rotenberg, chief programming executive and GM of children’s media and education for PBS. “While more can always be done, we’re excited to offer resources and games that more children can interact with.”

Pay it forward

With so much accessible TV experience and a first UDL-based game under its belt, Bridge is looking to keep helping TV producers and game developers who are considering accessibility in the early stages of projects rather than later on.

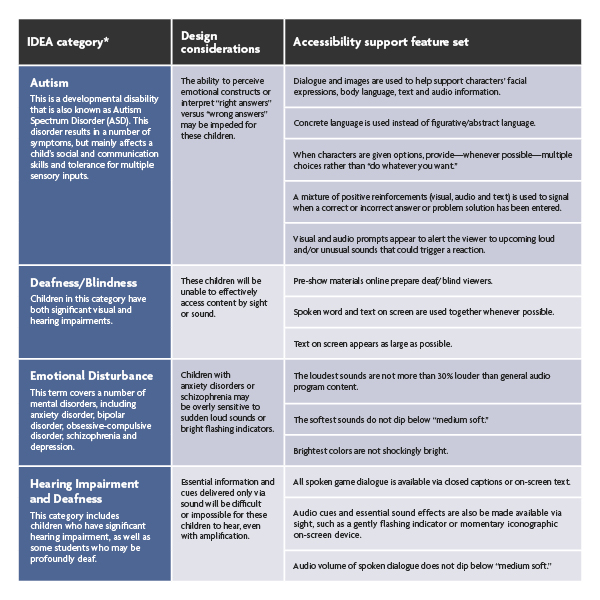

The company’s brand-new disability mapping guides—one for children’s television producers and another for children’s game developers—are currently in the final stage of review by the DOE’s Office of Special Education Programs, which partially funded the work. Once the guides are approved, they’ll go public this fall on the Bridge and WNET websites. (For a sneak peek, see below.) Bridge is also developing a companion document that takes a closer look at color blindness as it relates to educational gaming and children’s programming.

While the go-to manuals are a great first step, Sheppard reiterates how complicated it is to make accessible content from scratch.

“With Bridge as an advisor, we had about four or five people with different specialties all looking at the game through different lenses. First-timers will need to receive additional input from knowledgeable advisors because there isn’t one cookie-cutter approach,” she says.

Despite the challenges, Sheppard is excited by what her team will be able to integrate into other interactive games or TV series based on what they’ve learned. She’s also encouraged that a number of big tech companies, including Apple and Google, are starting to think about working with universities to ensure accessibility is baked into computer science degree programs.

“One of the challenges is that programmers don’t necessarily enter the field of kids development with this specific expertise. To see a change, we’ll need to see some embedding of accessibility training and learning in the next generation of scientists. There will be a need for more foundational change to trigger the ripple effect.”

Disability mapping guide for children’s TV producers

Source: Kidscreen