How Tech Leaders are Being More Inclusive and Satisfying Legal and Market Imperatives

September 10, 2018

Retiree Douglas Wakefield is a tech enthusiast.

The 76-year-old begins a typical day by donning his Apple Watch and listening to its synthesized voice deliver the weather. Over coffee, the Arlington, Virginia, resident catches up on overnight news on his iPhone X and consumes books read out loud on topics like coding – his goal is to write apps for the iPhone.

Blind since birth, Wakefield has been taking advantage of features on the most popular tech devices and platforms that have made them more useful to people with disabilities.

These have meant big changes in the way he goes about his daily routine. A former broadcaster for the Department of Agriculture and later a computer specialist working in government, he uses Microsoft's Seeing AI app for the iPhone to, among other purposes, scan barcodes that let him distinguish the groceries that are delivered: packages of crackers, or the Chardonnay his wife prefers to the Pinot Noir he favors.

Previously, someone would have to tell him and his wife, who is also blind, which bottle was which.

Thanks to narration tracks on Netflix and Apple TV, he can take in a movie, following audio that depicts the scenes, from what characters are wearing to their facial expressions. In 2016, Netflix reached a settlement with advocates for the blind community to add such "audio descriptions" tracks to more of the content.

One of the biggest shifts in Wakefield's day-to-day routine comes from the Amazon Echo, Google Home and Apple HomePod; he owns all three voice-activated smart speakers. For example, he can summon the assistants to turn on household lights by voice.

"I often say if all these tools were around when I was going to school, God, it would be a breeze," he says.

Over the last few years, Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft have leveraged artificial intelligence, computer vision and advances in voice recognition to deliver tools to assist blind individuals and people who are deaf, have motor impairments or other disabilities. At the same time, new technologies such as voice-activated speakers and more captioning on websites and in social media have widened access to some internet services.

Pressured to do the right thing

Development of these specialized features are driven by a confluence of factors – a desire by tech leaders to be more inclusive, but also the need to satisfy legal and market imperatives.

“This is the right thing to do both from a moral point of view but it’s also the right thing to do from a business point of view,” says Amazon director of accessibility Peter Korn.

Companies must adhere to the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act and comply with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, which requires the federal government to make electronic and information technology accessible to people with disabilities. And many states have their own Section-508-type requirements or consumer-protection statutes.

Laws have provided the biggest benefit to blind people, because “you can’t count on people’s compassion to drive industry,” says Anil Lewis, executive director for the Jernigan Institute at National Federation of the Blind.

Companies are also cognizant that to keep expanding their customer base, they need to make products that everyone can use.

More than a billion people, or about 15 percent of the global population, have some form of disability, according to the World Health Organization.

What's more, as the general population ages, “accessibility is not something that is strictly thought of anymore as helping people who are blind or helping people who are deaf,” says Geoff Freed, director of technology projects and web media standards at the National Center for Accessible Media. “When you make something accessible for a specific population, the entire population benefits.”

Built-in tools, not after-thoughts

But there's still plenty of room for progress across the tech industry.

Increased tech accessibility is needed to break down some of the barriers that prevent or make it difficult for people with disabilities to enter the workforce. In 2017, 18.7 percent of people with a disability were employed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported, compared to 65.7 percent for those without a disability. And the unemployment rate for people with a disability was 9.2 percent, more than double the 4.2 percent rate for the rest of the population.

Artificial intelligence promises to help predict consumers' needs, model human conversation and sort through vast tracts of data – all potentially helpful for people with disabilities.

But, "we’re still kind of at the starting line with AI in terms of what its promises are and what it will be able to deliver," said Eric Bridges, executive director of the American Council of the Blind.

Advocates also warn that technological innovations meant as conveniences must avoid conferring a stigma on the user.

“People want their accessibility tools to be built into the same devices that everybody else is using whenever possible, rather than have their own device that makes them stand out because of their disability,” says Eve Andersson, the director of accessibility engineering at Google.

Lewis of the Jernigan Institute was on a panel at an accessibility conference when an executive from IBM brought up the idea of an artificial intelligence robot that could help a blind person check into a hotel and show them around their room. While acknowledging it could be helpful for some, Lewis was insulted.

"Just give me the key. If I get to the hotel and expect this (AI robot) to take me to the room, that's going to make me lazy and not practice my independent travel skills. And one day that technology may not work or not be available."

What companies are doing

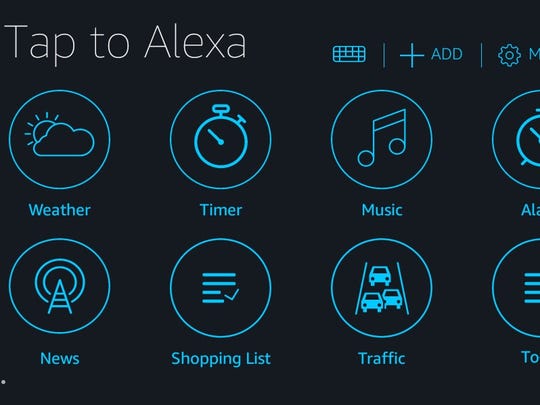

The Tap to Alexa feature on the Amazon Echo Show. (Photo: Amazon)

Microsoft recently came out with a $100 adaptive controller for the Xbox with multiple ports that are compatible with a range of optional accessibility peripherals, including bite switches, single-handed joysticks and foot pedals.

At its Build developer conference this past May, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella announced an “AI for Accessibility” pledge to spend $25 million over five years to put AI tools in the hands of developers who can accelerate the development of accessibility solutions.

At its own I/O developer conference last spring, Google revealed plans for a Lookout app coming later this year, which by employing machine learning and image processing, promises to help blind people wearing a Pixel around their neck learn about their environment. It uses spoken cues to describe where a bathroom is located or to detect people, text and objects around them (“scissors at 12:00.”)

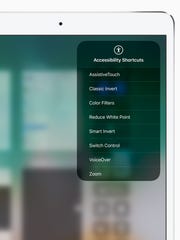

Some accessibility features are fairly simple -- on the iPhone, for example, a person with visual impairments can magnify the display or invert the screen colors to better make out the screen. Other tools on the phone are meant to help disabled users interact with switches and other adaptive accessories.

Wakefield, for instance, also uses a refreshable Braille display that helps him feel in Braille what is on the screen. "I don't care how good synthetic speech is, sometimes they can really botch a word." He joked that the Jewish holiday of Chanukah is always pronounced "chanookah."

An accessibility shortcuts menu on Apple's iPad Pro (Photo: Apple)

More than 50 third party Bluetooth hearing aid models work with Apple’s Made For iPhone hearing aid program which came out in 2013. Last year, Apple partnered with Cochlear on the first Made For iPhone cochlear implant. As part of the upcoming iOS 12 software update, consumers can also turn AirPods wireless earbuds into a hearing aid of sorts, using an Apple-developed assistive technology called Live Listen.

Amazon recently introduced a feature for the Echo Show smart speaker with a screen called Tap to Alexa, which lets people with speech impairments query Alexa without using their voice. Instead, they can tap the display and choose among preset menu options, maybe to have Alexa deliver weather or news. Folks can customize such requests too, perhaps using the Echo Show or Echo Spot to turn certain smart home devices on or off. Users of screen-based Echo devices can also turn on captioning.

Disability advocates say that ideally, companies will build assistive technology into their development process – rather than as an afterthought.

“What some tech companies do is say, `We’ll release an accessible version later, and we’ll talk about it like it’s something really sexy and, woohoo, exciting.’ We actually want (it) to be kind of boring” and just be accessible,” says Eve Hill, a partner at Brown, Goldstein & Levy in Washington, D.C., and former deputy assistant attorney general at the Department of Justice Civil Rights Division.

Don Barrett, a member of the American Council of the Blind, agrees: “If you get coders and computer scientists accessibility-aware from the beginning … it’s not a big deal.’ I think people just don’t think along those lines,” he said.

Apple CEO Tim Cook with actor and deaf advocate Nyle DiMarco making a surprise visit to California School for the Deaf in Fremont, Calif.) for the launch of the company's Everyone Can Code initiative in May 2018. (Photo: Apple)

That attitude is changing. Apple CEO Tim Cook has been pushing the company's "Everyone Can Code" curricula for the Swift programming language to schools across the country that serve students who are deaf and blind.

"At Apple, we consider accessibility to be a basic human right," says Sarah Herrlinger, director of global accessibility policy at the company.

And more tech companies have dedicated accessibility units.

Facebook's Matt King was recruited from IBM in 2015. A year later, his project at the social network began helping sightless or low-vision people “see” what’s in pictures by describing what’s in them. At the time, the photo descriptions were only available in English and only on iOS and Android; descriptions have since been rolled out to the Web and to more than two dozen languages.

Since then, Facebook has been expanding the kinds of audible descriptors it can identify, including such activities as sitting, eating, walking or playing a musical instrument. And in December, it started naming friends in a photo using facial recognition.

What's next?

Matt King, a Facebook accessibility engineer who has been blind since childhood, is working to create tools that will use artificial intelligence to identify objects in photos and describe them to users.Video by Christopher Schodt for USA TODAY

Though not ready to be commercialized, a New York developer Abhishek Singh built a prototype that lets Alexa devices with a camera detect sign language and respond with transcribed text.

Machine learning has “made it possible for the computer to see an image of me and continuously make a prediction of what sign it thought I was making,” Singh says. “The purpose of this project was to start a conversation, not solve the entire sign-language-to-text problem.”

And despite also being a work in progress, Microsoft’s Seeing AI app is also providing benefits to people like Wakefield. Among its features, the app uses the phone’s camera to describe a person’s approximate age and mood, though not always with perfect accuracy (e.g., “47-year-old man looking happy”). Seeing AI can also read text, identify currency and describe colors, which can help a blind person pick out a matching outfit.

Wakefield has one lasting complaint that people both with and without disabilities can relate to, the price of today's tech gear: "A lot of people can't afford this stuff. Seeing AI is free. But the iPhone isn't."

Source: USA Today